LOW-INCOME NEIGHBORHOODS no longer experience the levels of communitywide disinvestment that they did through the 1990s, but their residents still face significant poverty, risk of displacement, and limited economic mobility. For this reason, Change Capital Fund (CCF), a New York City donor collaborative, formed to invest in sophisticated community organizations that implement data-driven strategies integrating housing, education, and employment services to fight poverty. While government agencies are often constrained in providing one type of assistance — such as income support — to those who seek services from them, CCF embraces a more comprehensive approach that has the potential to reach underserved community residents.

This brief, the first of five by MDRC on CCF, gives an overview of the initiative and its goals, describes the grantees’ neighborhoods and their strategies to fight poverty, and highlights some of the early lessons from the initiative. Drawing on interviews, observations, programmatic data from each grantee, and outcomes data capturing the collective efforts of all grantees during the first of four years of CCF funding, the brief illustrates how community organizations may be uniquely positioned to undertake economic opportunity initiatives, if they can both reach underserved populations and mobilize and coordinate high-quality services for them.

The first year of CCF was a ramp-up year, with grantee efforts focused on building internal capacity and the appropriate infrastructure to put their respective interventions into place and scale them up over the next three years. These steps included hiring staff, adopting internal processes to make it easier to share knowledge, putting into practice new ways to coordinate service delivery, establishing data tracking systems, and defining outcomes to measure their work. CCF is a rare funding opportunity, providing financial support to grantees’ internal capacity-building efforts while also emphasizing rigorous outcomes measurement and tracking to enable grantees to demonstrate their success in serving neighborhood residents.

Change Capital Fund: An Innovation In Community Initiatives

A collaboration of 17 funders, the new CCF initiative is providing five community organizations with $1 million each over four years to make organizational investments that will help them expand economic opportunity in underserved neighborhoods. The funders believe that local nonprofits can play a key role in fostering economic mobility at the neighborhood level by reaching deeply to serve populations who would not otherwise be engaged and by coordinating multipronged services to help on a number of fronts.

CCF selected the five nonprofits, located in Brooklyn and the Bronx, for their strong community ties and good track record of providing services. They received funding to embark on their interventions in May 2014. The initiative emphasizes a “cross-sector” approach, using strategies in multiple domains: for example, combining and coordinating educational services, job training and placement programs, affordable housing development, and services to low-income tenants. In this way, CCF transcends the limits of more traditional funding streams that support a single program or service.

CCF was launched at a time of increased local and national interest in neighborhood effects on economic inequality and the role of neighborhood organizations in finding cost-effective solutions to reduce poverty. Recent research shows that neighborhoods matter for residents’ life prospects, over and above the effect of poverty alone. Recognizing these findings, some of the signature initiatives of the Obama administration — such as My Brother’s Keeper, a program to help young men of color, and the interagency Neighborhood Revitalization Initiative — include place-based strategies to improve outcomes for individuals and communities. CCF is distinguished from other community initiatives in several ways:

- THE EXTENT OF THE DONOR COLLABORATIVE.

CCF’s large collaborative of 17 donors has a wide array of expertise and a deep history of work within New York neighborhoods, with representation from banks, foundations, and intermediaries. This varied experience may help to avert conflict between grantees and funders about program expectations — a well-documented challenge in place-based programs. Additionally, the collaborative includes a representative from the New York City Mayor’s Office, which may help the initiative strengthen ties to municipal government. - A LONGER-TERM VISION OF ORGANIZATIONAL CHANGE.

As suggested by the name “Change Capital,” CCF has a longer-term vision of progress for New York’s community organizations. CCF formed in part from the belief that an exclusive focus on the physical revitalization of affordable housing may not be a sufficient antipoverty strategy. CCF therefore helps demonstrate for the community development field how to move toward sustainable business models, so that local organizations might be funded to provide social services, educational programming, and/or workforce development and take advantage of emerging revenue streams, such as the “pay-for-performance” model of public-private financing. - AN APPROACH THAT BLENDS CAPACITY BUILDING WITH BENCHMARKS BASED ON OUTCOMES.

Some community initiatives take an exclusively “capacity-building” approach, working with community organizations to develop their ability to provide or coordinate services. Others take an exclusively “outcomes-driven” approach, aiming to change neighborhood conditions by determining aggressive goals and holding partners accountable for reaching them. CCF blends these approaches by providing extensive technical assistance and funding for groups to enhance programming and to use data to improve practice, while also setting expectations about measuring and reaching antipoverty outcomes.

The Community Organizations, Their Neighborhoods, and Their Strategies

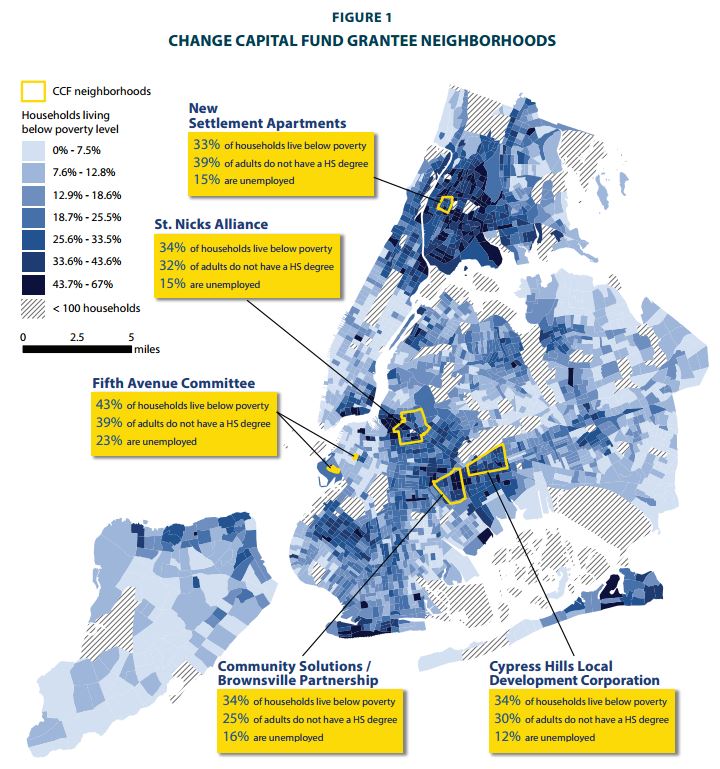

CCF selected five community organizations in some of the most impoverished areas in New York City. As shown in Figure 1, the poverty rates in these neighborhoods range from 33 percent to over 40 percent, and residents struggle with unemployment, underperforming schools, and higher crime rates than in other New York City neighborhoods.

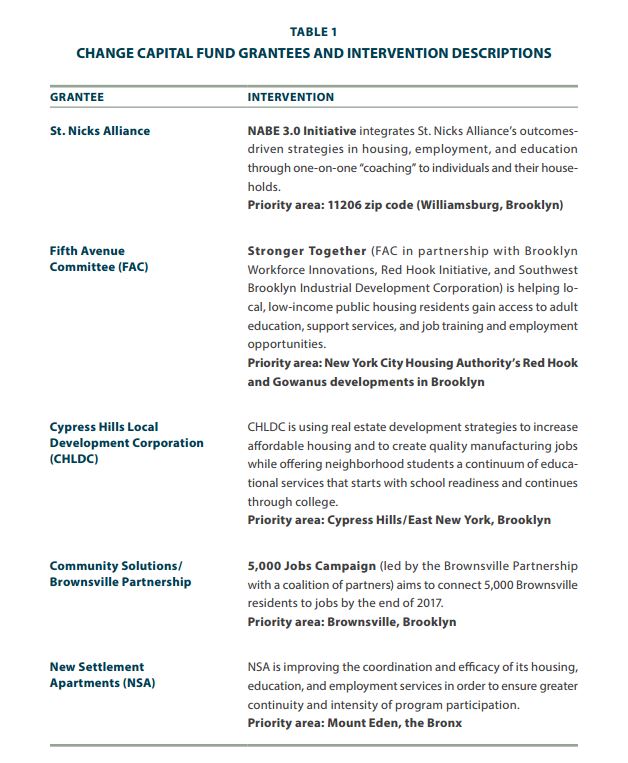

As shown in Table 1, the grantees — St. Nicks Alliance, the Fifth Avenue Committee, Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation, and Community Solutions/Brownsville Partnership, all in Brooklyn, and New Settlement Apartments, in the Bronx — deliver services related to housing, employment, and education. All aspire to integrate these services for the benefit of local residents.

Promising Strategies: Coordinated and Mobilized Resources to Foster Economic Opportunity

What distinguishes a community-based approach from other economic opportunity strategies, including those delivered by government agencies, such as workforce centers, or large institutions, such as public schools? One of the theories informing CCF is that community organizations are better positioned to coordinate services to low-income populations. Lowincome households often face needs on a variety of fronts, including the educational needs of children and the workforce needs of parents. Taking a multipronged approach may also reach multiple generations within the household, an important strategy because of the demonstrated relationship between parental and child outcomes. In contrast to larger organizations that may be accustomed to “working in silos” — rather than sharing information across sectors — and which are often constrained in the way they manage services, entrepreneurial organizations with strong community ties may be more flexible in providing or directing services to multigenerational households in an integrated way.

While typical funding streams pay for one service or support one program, CCF funds and enables its grantees to dedicate time to silo-busting efforts, such as intentionally combining and coordinating services or identifying and tracking outcomes that cut across an organization’s programs. In the first year of CCF funding, with plans to scale up interventions over the next three years, groups have made strides toward this vision of coordinated service delivery:

- INTEGRATING SERVICES, FROM THE TOP DOWN AND THE BOTTOM UP.

Program directors’ meetings at New Settlement Apartments and at Cypress Hills Local Development Corporation now include in-depth, rotating presentations on the varied services provided within each agency. This new format, implemented during the first year of CCF, allows directors to learn more about the services offered by other programs, their accomplishments, the challenges they face, and the potential for coordination with them. At a recent learning session, for example, Cypress Hills frontline staff made a presentation to program directors explaining some of the challenges they face in their high school equivalency program work. New Settlement held a two-day retreat to pilot a new, “whole-family” initiative, developing plans to collaborate, improve internal and external communications, and collect and manage data in a unified way. - DEVELOPING A SERVICE MENU FOR NEW CLIENTS AND CREATING VEHICLES FOR COORDINATING ACROSS AGENCIES.

To initiate and simplify collaboration among the four members of the Stronger Together partnership, a coordinator at the Fifth Avenue Committee created a one-page list outlining the services provided by each partner. This spurred the organizations’ frontline staff to make 110 referrals across partners as of March 31, 2015. Currently, Stronger Together partners track participants’ use of coordinated services with an informal, shared Google document, on which staff members across partner organizations have received training to ensure that data are input uniformly. - INITIATING WHOLE-FAMILY INTERVENTIONS.

St. Nicks Alliance hired two “transformational coaches” to work with neighborhood residents engaged in their after-school and employment programs during the first year of CCF funding. The coaches share an office and perform intake sessions using a form that allows each coach to assess whether someone in the family needs services from the other coach’s division. After intake, coaches conduct case conferences to discuss how to best serve the whole family in a coordinated and effective manner, developing a service plan to promote accountability (an example of silo busting). In the first year, St. Nicks Alliance was able to help 15 individuals secure a job, and 10 others are in the process of being placed. St. Nicks Alliance cultivated a relationship with a local real estate developer and opened 40 construction positions to its participants in fall 2015. Meanwhile, over 70 percent of the at-risk youth involved in St. Nicks Alliance’s NABE 3.0 after-school programming have improved or maintained their report card grades and attendance rates. Most remarkably, St. Nicks reports that the participants of its after-school program have increased their reading ability an average of 3.5 reading levels. More young people have since joined the promising program, and St. Nicks plans to increase the size of the program to meet the needs of more neighborhood residents.

Another reason that community organizations may be well situated to implement economic opportunity programs is that they may mobilize resources to reach underserved populations. Community groups have ties to local residents who might not otherwise be served, as well as connections with elected officials and government agencies that have resources that might be directed to these residents. CCF grantees have made headway:

- REACHING DEEPLY INTO NEW YORK’S POOREST NEIGHBORHOODS — INTO ITS PUBLIC HOUSING.

During its first year, Stronger Together hosted two events in the Red Hook and Gowanus public housing developments to introduce residents to the collective’s services. The events attracted Brooklyn-based New York City Council members, who have pledged resources to the collaborative, and also media attention. As a result of these events and additional outreach in the developments, Stronger Together partners served just under 200 residents in their first year in collaboration with each other — contributing to the total of 4,655 residents served by grantees in CCF-related work across all five neighborhoods during the first year of CCF funding. - BRINGING ATTENTION AND JOB OPPORTUNITIES TO NEIGHBORHOODS LIKE BROWNSVILLE.

In the first year, the Community Solutions/Brownsville Partnership established relationships with service organizations, city and state workforce, housing, and public assistance agencies, and private businesses to create an employment pipeline for local residents. Putting these relationships into practice, the partnership hosted its first on-site recruitment event in December 2014, with résumé assistance, interview preparation, and referrals for attendees who were not immediately ready to work. (This structure ensures that all residents who attend can benefit, regardless of where they are in the job-seeking process.) Eleven residents gained employment that week, contributing to the 403 total job placements reported across all CCF grantees during the first year. - KEEPING ON TOP OF MAJOR NEIGHBORHOOD CHANGES.

In the winter, New Settlement Apartments (NSA) sponsored a community forum on potential changes to the neighborhood, which was attended by over 400 community residents despite one of the biggest snowstorms of the year. Working across internal departments to encourage turnout, the staff hosted a crowd spanning an impressive age range, from middle school students to more elderly residents. Notable attendees included the area’s congressional representative, state and local elected officials, and the New York City public advocate. Over the course of the year, NSA’s tenant organizing initiative, Community Action for Safe Apartments (CASA), has served more than 750 local residents, with more than 65 tenant association meetings in over 20 buildings. CASA also held a workshop series covering a wide range of housing issues that attracted 267 attendees and hosted a free Housing Legal Clinic (with CASA partners and other local providers) that served 171 tenants.

Early Challenges

While it remains early in the initiative, grantees have identified a number of issues they have started to address.

- BUILDING DATA SYSTEM CAPABILITY.

Using data in a new way, to track organization-wide efforts, requires a different set of skills, from determining what data need to be collected and establishing how to collect the data to making decisions about the structure of the database and training program-level staff members in its use. Some CCF groups are starting to build these data systems from scratch, while others are attempting to build on existing databases. Building customized systems that track efforts across programs (usually not paid for by program grants or government contracts) can be difficult and expensive, given the number of services provided by organizations, outcomes to be tracked,and deliverables to be produced. In some instances, organizations use multiple databases, making data integration even more challenging. For example, Cypress Hills operates 12 databases across its programs — 11 of which are funder-mandated. - PUTTING SERVICE INTEGRATION INTO PRACTICE.

While grantees see the benefits of coordinating services to low-income families, a household’s needs may not be met by the community group’s services alone. Groups are finding that they need to develop standards and guidelines for assessment and referrals, both within agencies and outside them, so as to serve resident needs most effectively. - STARTING TO OPERATE ON A LARGER SCALE.

Sites generally used the first year to hire staff, develop procedures for coordinating services, and operate pilots of services. A lesson learned from Jobs-Plus, a placebased employment program for residents of public housing that raised earnings in public housing developments, is that reaching a significant level of “saturation” of services is important in achieving impacts.9 As grantees make the transition from the planning and early implementation “ramp-up” mode documented in this brief to a greater focus on outcomes, it will be important to assess how deeply saturation has reached within neighborhoods, and what resources may be required to operate at desired levels

Looking Forward

As CCF grantees continue to pursue their strategies to create communities of opportunity, MDRC will document their efforts and share lessons with practitioners, policymakers, funders, academics, evaluators, and individuals interested in neighborhood-based antipoverty programs. The next brief, expected in early 2016, will describe how CCF grantees and their partners best integrate and coordinate services and will draw more heavily on outcomes data. Future briefs will address how funders best support this ambitious work, how grantees build effective data systems, and what policy opportunities exist to support and scale up community-led work.